Perianal complications caused by

gluteal injection

Perianal complications caused by

gluteal injection

of modeling agents

![]()

Sergio Martínez-Millán, Julimar Briceño, Peter Pappe, Luis Angarita

Coloproctology Unit, General Surgery Service, La Trinidad Medical Teaching Center, Caracas, Venezuela

Perianal complications caused by

gluteal injection

Perianal complications caused by

gluteal injection

of modeling agents

![]()

Sergio Martínez-Millán, Julimar Briceño, Peter Pappe, Luis Angarita

Coloproctology Unit, General Surgery Service, La Trinidad Medical Teaching Center, Caracas, Venezuela

ABSTRACT

In this report we present three patients with late perianal inflammatory conditions that occurred after the administration of unidentified gluteal modeling agents (MA). The initial diagnosis was incorrect because the administration of these agents was not investigated during the initial evaluation. We recommend asking patients with inflammatory anal pathologies, especially those with an unusual course, about the administration of MAs to the buttocks. This approach may contribute to the effectiveness of the diagnosis of perianal conditions characterized by inflammation, although unusual in appearance.

Keywords: diseases of the anus, adverse effect, foreign body reaction, buttocks fillers, modeling agents

INTRODUCTION

Subcutaneous injection of modeling agents (MA) has been used in plastic surgery and aesthetic medicine to restore or improve body silhouette. The substances injected are varied: dimethylsiloxane (silicone), mineral oils (petrolate or paraffin), vegetable and even industrial oils, hyaluronic acid and collagen, among others.

The adverse effects and complications after the application of these agents have received different names: oleoma, paraffinoma, siliconema, iatrogenic allogenosis, modeling disease and reaction to MA.1,2

This article reports the late appearance of perianal alterations after gluteal injection of MA. The coloproctologist should consider this possible diagnosis in patients with this history who present inflammatory processes of the perianal region with an unusual clinical course.

CASE 1

A 50-year-old male patient, who has sex with men, consulted for a perianal tumor with seropurulent discharge. He had a history of HIV infection since 2001 and perianal HPV treated with local agents. Likewise, he mentioned having received an injection of MA in both buttocks, but did not indicate precisely the type of agent applied, nor the time that had passed since the administration.

Physical examination revealed warty condyloma-type lesions in the perianal region and a 1-cm nodular lesion on the posterior anal verge. Seropurulent fluid spontaneously oozed from this nodule. On anoscopy, warty lesions were observed in the anal canal. The initial diagnosis was anorectal fistula and peri- and intra-anal condylomata acuminata.

The intraoperative findings confirmed the condylomatous lesions. However, the orifice of the perianal nodule communicated with a cavity located in the coccygeal region. No other tract to the buttocks or anus was identified. The warty lesions were sectioned and fulgurated. The tract and coccygeal cavity were unroofed and debrided, draining abundant mucoid material. A biopsy was taken from the cavity wall (Fig. 1).

The final histopathological diagnosis, instead of anorectal fistula, was foreign body reaction (modeling agent) and condyloma acuminata with high-grade dysplasia.

During the postoperative period, the wound was treated with water-soluble dressings until the cavity healed in approximately four weeks (Fig. 2). Given the absence of acute phlogosis and the local nature of the foreign body reaction, no systemic medications were administered.

Figure 1. Case 1. Debridement material from a coccygeal cavity arising after administration of modeling agents to the buttocks. A fatty vacuole corresponding to the exogenous material is observed, surrounded by a neutrophilic and lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate. (Source: María Eugenia Orellana, Pathological Anatomy Service, Centro Docente Médico La Trinidad).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Sergio Martínez-Millán: msa2505@gmail.com

Received: February 2023. Accepted: February 2023

Sergio Martínez-Millán: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4250-6432, Julimar Briceño: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9543-931X, Peter Pappe: https://orcid.org/ 0000-0002-4288-0873,

Luis Angarita: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1934-4201

Figure 2. Case 1. A. Postoperative appearance of the incision and debridement of the coccygeal cavity. B. Mucoid material in the cavity.

C. Almost complete healing at the third postoperative week.

The patient presented on the tenth postoperative day with severe pain in the surgical site and left buttock, where an erythematous area measuring 8 x 10 cm, with a hard consistency and delimited edges, was observed. The diagnostic impression was a postoperative abscess. However, there was no leukocytosis (9,062 leukocytes/mm³) or neutrophilia (neutrophils 53%). Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis ruled out an abscess and showed the presence of foreign bodies in the gluteal regions compatible with MA. The patient was re-interrogated and reported the application of MA in both buttocks eight years earlier, which allowed the diagnosis of perianal allogenosis in the postoperative period for the anorectal fistula.

In a multidisciplinary meeting with Plastic/Reconstructive Surgery and Internal Medicine, methylprednisolone 16 mg/day for one week was indicated, with progressive improvement observed. Six weeks after the initial surgery, the seton was removed and a transanal mucosal advancement was performed. At 6 months of follow-up there is no recurrence of the fistula or AM lesion.

CASE 3

A 37-year-old woman presented with severe proctalgia for two days that increased with defecation and a fever of 38.5°C. Past medical history was not relevant. On physical examination, an increase in volume and slight erythema was observed in the right buttock, in the area corresponding to the ischiorectal fossa, which was painful on pressure. Anoscopy was omitted due to pain. The rest of the physical examination was not relevant. The laboratory showed a leukocyte count of 11,100 leukocytes/mm³ with neutrophilia of 89.8%, without other alterations.

The preoperative diagnosis was right ischiorectal abscess. However, during digital rectal examination and anoscopy performed under anesthesia, only a small cavity containing approximately 30 ml of seropurulent fluid was found in the right ischiorectal fossa, without communication with the anal canal. Its characteristics did not seem to correspond to an abscess of cryptogenic origin.

The cavity was debrided and the patient was discharged the next day. Because the intraoperative findings did not correspond to an anorectal abscess and the bacteriological analysis of the drained fluid did not report bacterial growth, the patient was questioned again 72 hours later. She reported injecting MA into both buttocks some years earlier,

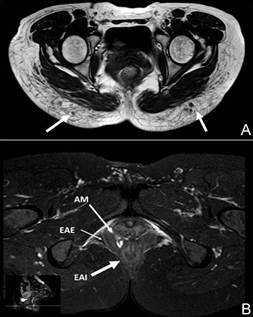

although she did not know the type. MRI of the pelvis showed hypointense images corresponding to MA in both buttocks and the right perianal area (Fig. 3), diagnosing perianal allogenosis.

Since phlogosis improved after the surgical procedure, no other adjuvant treatment was indicated. After one year of follow-up there is no recurrence of the described clinical condition.

Figure 3. MRI of the pelvis. A. Axial T1 sequence showing rounded hypointense images in the subcutaneous tissue of both gluteal regions, in relation to the presence of modeling agents. B. Axial T2-weighted SPAIR sequence showing signal hyperintensity consistent with modeling agents (AM), between the internal anal sphincter (EAI) and the external anal sphincter (EAE). (Source: Yariadny Ramírez, Programmed Radiodiagnosis Care Residence, Centro Médico Docente La Trinidad).

DISCUSSION

Depending on their nature and integration in the body, MA can be biostimulants, temporary or permanent.3

Biostimulant agents, such as polylactic acid and calcium hydroxyapatite, exert their modeling effect indirectly, since they cause an increase in volume by promoting the formation of collagen at the injection site. Temporary agents include hyaluronic acid and different collagens depending on the origin (bovine, porcine or human). Permanent agents include paraffin, silicone, and polymethylmethacrylate, among others. Although biostimulant agents and temporary agents can cause complications, their frequency and severity are less compared to those caused by permanent MA. The latter are involved in the majority of adverse effects reported in the literature.

Depending on the time of appearance, these adverse effects have been classified as early (before 14 days), late (between 14 days and one year) and late (after one year).

Once these manifestations appear, they may follow a nonspecific recurrence pattern. All our cases presented late reactions. Therefore, patients did not necessarily associate them with the application of MA to the buttocks and consulted the coloproctologist for symptoms referring to the anorectal region. These late complications may present as chronic suppurative conditions (Case 1, in which perianal allogenosis was mistaken for an anorectal fistula) or acute suppurative conditions (Cases 2 and 3 with initial diagnosis of postoperative and cryptogenic abscess, respectively). These anorectal conditions present clinical characteristics such as palpation of a tract, in the case of fistula, or the presence of defined cavities with frankly purulent content, characteristic odor and positive cultures in the case of abscesses, clinical facts that we do not observe in our patients.

On the other hand, the development of perianal complications secondary to MA injection into the buttocks may follow an atypical course. This occurred in the second patient, who presented a “postoperative abscess” after exploration and placement of a loose seton in a fistulous tract, an unusual complication of this surgery, if performed correctly.

In the two cases of acute presentation (Cases 2 and 3), the triggers are unclear. In our second patient, we believe that the long and excessive instrumentation of the anorectal fistula tract caused the inflammatory response. It should be noted that the fistula was of cryptoglandular origin and not related to the presence of the MA. Finally, in the third patient we could not identify any trigger.

Another aspect that we believe may affect the pathophysiology of perianal allogenosis is the possible displacement of the MA towards that area due to proximity, giving rise to the appearance of symptoms typical of anorectal inflammatory processes. The displacement of the MA to other neighboring areas, such as the lumbar region, has already been described.4

Regarding the use of paraclinical methods, imaging studies (soft tissue ultrasonography, computed axial tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) offer the best diagnostic option to identify the presence of MA, either at the injection or migration site. On MRI, MA are observed as hypo or hyperintense lesions, depending on the MRI sequence used. Different infiltration patterns have been described: globular, linear, pseudonodular, diffuse or mixed. Furthermore, when macrophages contain MA it is possible to observe infiltration of regional lymph nodes.5 Likewise, it is possible to identify signal intensity values that suggest the type of MA, even if the patient is unaware of the substance applied. We confirm the effectiveness of this study to identify the presence of MA and rule out migration to deep and neighboring tissues.

To conclude, with the purpose of reporting perianal complications secondary to the administration of MA in the buttocks, we present three patients initially misdiagnosed as fistula and/or anorectal abscesses of cryptogenic or postoperative origin. There were no palpable fistulous tracts

and the supposed external opening did not communicate with the anal canal. We also did not find delimited cavities with purulent content and the culture did not show bacterial growth. Likewise, the clinical course was unusual because they did not evolve as expected for the supposed initial diagnoses. Furthermore, no patients mentioned MA injection into the buttocks when asked about their relevant medical history during the baseline interview.

Therefore, we recommend that the coloproctologist ask about the application of MA into the buttocks, since patients hide this practice or do not consider it worthy of mention. This directed questioning is of special importance, especially in the evaluation of patients with symptoms and signs of perianal infectious with unusual characteristics and clinical course.

REFERENCES

1. Martínez-Villarreal AA, Asz-Sigall D, Gutiérrez-Mendoza D, Serena TE, Lozano-Platonoff A, Sanchez-Cruz LY, et al. A case series and a review of the literature on foreign modeling agent reaction: an emerging problem. Int Wound J. 2017; 14:546-54.

2. Coiffman F. Alogenosis iatrogénica: Una nueva enfermedad. Cir Plast Iberolatinoam. 2008; 34:1-10.

3. Bachour Y, Kadouch JA, Niessen FB. The aetiopathogenesis of late inflammatory reactions (LIRS) after soft tissue filler use: a systematic review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2021; 45:1748-59.

4. Soliman SB. Liquid silicone filler migration following illicit gluteal augmentation. Radiol Case Rep. 2023; 18:984-90.

5. Gonzalez-Hermosillo LM, Ramos-Pacheco VH, Gonzalez-Hermosillo DC, Cervantes-Sanchez AM, Vega-Gutierrez AE, Ternovoy SK, et al. MRI visualization and distribution patterns of foreign modeling agents: a brief pictorial review for clinicians. Biomed Res Int. 2021; 2021:2838246.