CASE REPORT

Perineal hernia secondary to Miles operation. Report of two cases

Gerardo Martín Rodríguez* MSACP MAAC MASCRS, Camilo Sebastián Canesín MAAC*, Ezequiel Palmisano MAAC**

Digestive Endoscopy and Minimally Invasive Surgery Unit, Clínica Del Angelo and Clínica Sarmiento, Formosa, Argentina

* Staff Surgeon

** Consultant Surgeon, Universidad Nacional de Rosario

ABSTRACT

Perineal hernia is a rare and possibly underestimated complication of abdominoperineal resection. In recent years, its incidence has increased, probably due to the adoption of the extra-elevator technique and preoperative chemoradiotherapy.

It can be treated by the perineal, abdominal or combined approach with similar results, without obvious advantages of one technique over another, so it must be adapted to each particular case. The use of mesh has replaced the primary suture. There is a lack of data to support the usefulness of prevention techniques.

We contribute to the literature 2 cases of symptomatic perineal hernia in 23 (8.6%) patients operated on by Miles operation who required surgical repair. A male patient underwent a perineal approach and a female patient a laparoscopic abdominal approach, reinforcing the pelvic floor with mesh in both. They had a good postoperative outcome, with no recurrence at 12 months.

We encourage collaborative work in Argentina that can provide more robust data.

Keywords: perineal hernia, abdominoperineal resection, repair

INTRODUCTION

Perineal hernia (PH) is defined as a defect in the pelvic floor through which intrabdominal viscera can protrude.1,2 It can be primary (congenital) or secondary (postoperative). The initial report is attributed to De Garangeot in 1743. Moscowitz pioneered surgical treatment in 1916, and Yeoman described postoperative PH in 1939.

Different approaches and techniques are proposed for its resolution, although none is considered the gold standard of treatment.1-6

Correspondence: Dr. Gerardo Martín Rodríguez – Avenida Italia 1654 1º Piso - CP 3600 – Formosa (Formosa) – drgmrodriguez@yahoo.com.ar – drgmrodriguez@gmail.com FP: Dr. Gerardo Martín Rodríguez Phone: 0370- 4421024

ID ORCID: Gerardo M. Rodríguez 0000-0002-0302-2518, Camilo Canesín 0000-0002-1529-2662,

Ezequiel Palmisano 0000-0003-4529-7496

We present the experience of our group in the approach to 2 patients with symptomatic PH. The incidence was 8.6%, 2 out of 23 patients who underwent a Miles abdominoperineal resection between 2005 and 2021.

CASE 1

A 60-year-old man with a history of chronic smoking, arterial hypertension, and anal adenocarcinoma, consulted for a progressively growing perineal bulge (Fig. 1) and discomfort in the region, after 7 months of Miles laparoscopic surgery with primary closure of the perineum.

Figure 1. Case 1: Perineal hernia 7 months after Miles operation for anal adenocarcinoma.

Physical examination revealed a reducible PH, with intestinal content, confirmed by computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis (Fig. 2).

The reconstruction was performed through a perineal approach. After opening the sac and reducing the contents (intestinal loops and greater omentum), the perineum was reinforced with a double-layer mesh (Polyester + resorbable film of porcine collagen, polyethylene glycol and glycerol) (Fig. 3). The mesh was fixed to bony landmarks (ischial tuberosities and coccyx) and pelvic floor muscles with a fixation device, interposing the greater omentum.

The postoperative period was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the 3rd postoperative day. The patient did not comply with adjuvant therapy and developed lung metastases, dying 18 months later due to disease progression, with no perineal symptoms.

Figure 2. Case 1: Computed tomography showing the perineal hernia and its contents.

Figure 3. Case 1: Hernia repair by perineal approach. A. Hernial sac protruding after skin incision. B. Content of intestinal loops. C. Mesh placed. D. Final appearance with sutured skin.

CASE 2

A 58-year-old woman, with no history of interest except for laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection with primary closure of the perineum due to lower rectal adenocarcinoma, consulted the 4th postoperative month due to progressively growing perineal bulge, dysuria, and local discomfort.

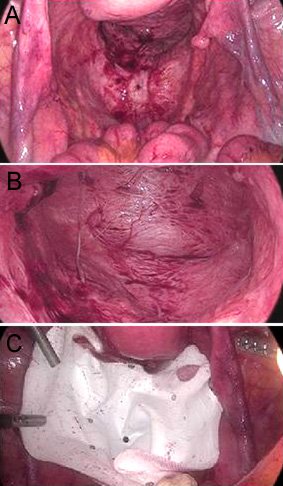

Reducible PH was diagnosed (Figs. 4 and 5) and repaired by a laparoscopic abdominal approach.

Figure 4. Case 2: Perineal hernia 4 Figure 5. Case 2: Computed tomography,

months after a Miles operation for sagittal section. Perineal hernia is shown.

adenocarcinoma of the rectum.

A. Posterior view. B. Anterior view.

After releasing few loose adhesions, the content was reduced to the abdominal cavity and the pelvic floor was repaired with a double-coated mesh, fixed to the bone and muscle with a fixation device, without omentoplasty (Fig. 6).

The patient was discharged on the second postoperative day. No recurrence was observed at 12-month follow-up (Fig. 7).

DISCUSSION

HP is classified as anterior (it appears in front of the transverse perineum muscle) and posterior (it appears at the level of the levator ani muscle or between it and the coccygeal muscles).

Secondary PHs are true incisional hernias in which the defect is at the surgical incision and the contents of the hernial sac are usually the small intestine.2,4

After cylindrical or extra-elevator abdominoperineal resection, the occurrence of perineal complications is relatively frequent. Infection and dehiscence of the perineal surgical site or pelvic abscess formation prolong care and may cause late complications such as perineal hernia.

Since Miles's original description, management of the perineum has been controversial. Traditionally, the wound was left open and packed with gauze, or only partially closed. Since the mid-1960s, perineal wound closure has been advocated, with debate as to whether or not leaving the pelvic peritoneum open improves healing. Currently, primary closure is the most widely used method. (4)

Figure 6. Case 2: Hernia repair by laparoscopic abdominal approach. A and B. Intra-abdominal view of the hernia. C. Mesh placement.

PH has no gender preference and its incidence is reported to be between 1 and 26%, with a recent increase attributable to the practice of the extra-elevator technique.

HP appears mainly in the first postoperative year.3,6 Some authors suggest that it may be more common in the laparoscopic approach (possibly due to less adhesion formation) and/or after neoadjuvant therapy.

Potential risk factors mentioned are: age over 60 years, obesity, neoadjuvant therapy, malnutrition, smoking, diabetes, chronic diseases causing ascites (possibly due to increased intra-abdominal pressure), elongated mesentery, perineal wound infection, failed peritoneal closure, excision of the levators, and prior hysterectomy.2-5

Figure 7. Case 2: A. Perineal hernia before surgery. B. After surgical repair.

The most commonly reported sign is the presence of a lump in the perineum with or without skin erosion, usually painless. When the bladder is involved, dysuria and increased voiding frequency occur. Dyspeptic disorders caused by traction or compression of the omentum and intestinal loops are rare.

The most serious complications, such as intestinal obstruction and strangulation, are infrequent due to the wide neck of the hernia and the destruction of the pelvic floor.

The diagnosis is made with the clinical history and physical examination that is typical. PH may be reducible or irreducible, and imaging (ultrasound of the perineal region, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging) usually confirms the defect and identifies herniated organs.

Irreducible PHs must be differentiated from cysts, lipomas, and other superficial tumors.

Regarding management, if the hernia is asymptomatic or causes little discomfort, or in patients with a high risk of postoperative complications, observation and control with support measures are recommended. There are no data to suggest that repair of asymptomatic PH decreases the rate of complications.4

The most radical treatment is surgical repair. In case of acute evisceration of the abdominal contents, urgent intervention is indicated, with reduction of the contents and tamponade. Various techniques and approaches are used, generally guided by the size of the hernia, the contents of the sac, and the magnitude of the symptoms. The approach can be perineal, abdominal, or combined, with or without mesh placement.

Basic maneuvers include content reduction and defect repair.3-7,10 The perineal approach is reported to be the least invasive, with rapid recovery and low risk of postoperative complications. It can be performed with a vertical or elliptical incision directly over the defect, identifying and reducing all the hernial content, repairing and closing the sac if it exists. By fixing the mesh to firm structures (coccyx, ischial tuberosities and pelvic floor muscles) exceeding the defect with some tension, better pelvic floor support is achieved.

The abdominal approach allows exploring the entire abdominal cavity and is especially useful in cases of obstruction where intestinal viability must be assessed. It is also indicated in recurrent hernias or when there is an associated disease. The laparoscopic approach has proven to be safe and effective.3,8-10 It can also be carried out using a robotic approach.11 The combined approach is considered when it is not possible to completely reduce the contents and perform adequate lysis of adhesions by a single approach.

Tissue repair or mesh placement may be necessary, as in most cases closure of the perineum is difficult because the edges cannot be brought together without tension and this carries a higher risk of recurrence.12

When simple suturing of the perineal wound is not possible, an autologous tissue flap or a prosthetic mesh may be necessary to repair the defect. For the first option, there are intra-abdominal organs (bladder, uterus, and cecum) that reduce the risk of hernia but do not strengthen the pelvic floor. Another option is to mobilize the greater omentum, especially in cases of infection that do not allow the use of a mesh. Reconstruction with fasciocutaneous or myocutaneous flaps (gluteus, gracilis, tensor fasciae latae, or rectus abdominis) is a good option for patients at risk of local infection, although it requires training in advanced techniques, including microsurgery.2 The use of prosthetic materials arose from the need of simple procedures that increase tissue resistance and avoid tension in neighboring structures. Biological meshes have the ability to embed themselves in local tissue, promote neovascularization, be less prone to infection, and cause few adhesions, although they appear to have high recurrence rates.5,7 Many surgeons prefer to place synthetic meshes, even more so if it is possible to perform an omentoplasty to separate them from the intestine. Slow-absorbable, non-absorbable sutures or fixation devices are used for its fixation.

There is no gold standard approach or technique for PH repair, and each has advantages and disadvantages (Table 1).

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of the different surgical approaches for the repair of a perineal hernia.

|

Approach |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Abdominal open |

Allows the semiology of the entire abdominal cavity Greater familiarity of surgeons |

Longer length of stay Increased postoperative pain More invasive |

|

Abdominal laparoscopic |

Allows the semiology of the entire abdominal cavity Minimally invasive Quick postoperative recovery |

Requires proficiency in laparoscopic surgery Ergonomic limitations in dissection of the pelvis |

|

Perineal |

Better control of the perineal region Does not require general anesthesia |

Limited surgical field for the abdominal cavity |

A systematic review of the literature between 1946 and 2016, of 21 studies with 108 patients, reported that the approach was perineal in 69% of cases, laparoscopic abdominal in 23%, conventional abdominal in 3%, combined laparoscopic in 3%, and combined conventional. in 2%, observing a growth of the laparoscopic approach and the use of different types of meshes to the detriment of the primary closure of the defect.1 In our group, the decision on the approach was made based on the biomorphological characteristics of the patient, experience in laparoscopic surgery, and the availability of mesh.

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons proposes a practical management algorithm for different situations (Fig. 8).3

Recurrence, reported between 16.6 and 100%, is attributable to the anatomical complexity of the area and to hyper pressure from bipedestation. It is difficult to know the real rate of recurrence due to the low number of published cases and the lack of clarity regarding the repair methods.4

To reduce the incidence, prevention is important, for which the technical principles to follow are careful closure of the surgical wound, meticulous hemostasis, placement of a suction pelvic drain, and avoiding fecal contamination. The performance of myocutaneous flaps or the placement of prophylactic meshes can contribute, although the scientific evidence in this regard is still scarce.3,4,12

The

patients resolved in our surgical group had a good postoperative outcome and

both the perineal approach and the laparoscopic abdominal approach were

feasible and safe.

SYMPTOMATIC PERINEAL HERNIA

(Physical exam ± Imaging studies)

|

Evidence of incarceration or strangulation?

NO YES

|

|||

|

|||

Individualized treatment

Cost/Benefit

Clinical follow-up Conservative Elective surgery

treatment

|

Is it necessary to repair another hernia

or perform extensive adhesiolysis?

![]()

![]() NO

YES

NO

YES

PERINEAL APPROACH COMBINED APPROACH

OR

ABDOMINAL APPROACH

ABDOMINAL APPROACH

- Conventional

-

Laparoscopic

Laparoscopic

|

REPAIR TECHNIQUE

|

|

MESH

- Synthetic

- Biological COMBINATION Mesh + Flap AUTOLOGOUS TISSUE FLAPS - Fasciocutaneous

- Myocutaneous

Figure

8. Diagnostic

and therapeutic algorithm. Adapted from Jurkeviciute and Dulskas.3

REFERENCES

1. Balla A, Bautista Rodríguez G, Buonomo N, Martinez C, Hernández P, Bollo J, et AL. Perineal hernia repair after abdominoperineal excision or extralevator abdominoperineal excision: a systematic review of the literature. Tech Coloproctol. 2017: 21:329-36.

2. Yasukawa D, Aisu Y, Kimura Y, Takamatsu Y, Kitano T, Hori T. Which therapeutic option is optimal for surgery-related perineal hernia after abdominoperineal excision in patients with advanced rectal cancer? a report of 3 thought-provoking cases. Am J Case Rep. 2018; 19:663-68.

3. Jurkeviciute D, Dulskas A. Diagnosis and management of perineal hernias. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022; 65:143-47.

4. Uriarte Vergara B, Zorraquino González A, Gutiérrez Ferreras AI, Roca Domínguez MB, Pérez de Villarreal Amilburu P. Hierro-Olabarria Salgado L. Actualización en el manejo de la hernia perineal secundaria: experiencia en una Unidad de Pared Abdominal con una serie de casos. Rev Hispanoam Hernia. 2021; 9:220-31.

5. Blok RD, Brouwer TPA, Sharabiany S, Musters GD, Hompes R, Bemelman WA, Tanis PJ. Further insights into the treatment of perineal hernia based on a the experience of a single tertiary centre. Colorectal Dis. 2020; 22:694-702.

6. Stamatiou D, Skandalakis JE, Skandlakis LJ, Mirilas P. Perineal hernia: surgical anatomy, embriology and technique of repair. Am Surg. 2010; 76:474-79.

7. Morales-Cruz M, Oliveira-Cunha M, Chaudhri S. Perineal hernia repair after abdominoperineal rectal excision with prosthetic mesh-a single surgeon experience. Colorectal Dis. 2021; 23:1569-72.

8. Goedhart-de Haan AMS, Langenhoff BS, Petersen D, Verheijen PM. Laparoscopic repair of perineal hernia after abdominoperineal excision. Hernia. 2016; 20:741-46.

9. Ghellai AM, Islam S, Stoker ME. Laparoscopic repair of postoperative perineal hernia. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002; 12:119-21.

10. McKenna NP, Habermann EB, Larson DW, Kelley SR, Mathis KL. A 25 year experience of perineal hernia repair. Hernia. 2020; 24:273-78.

11. Maurissen J, Schoneveld M, Van Eetvelde E, Allaeys M. Robotis-assisted repair of perineal hernia after extralevator abdominoperineal resection. Tech Coloproctol. 2019. doi:10.1007/s10151-019-01969-0.

12. Maeda Y, Espin-Basany E, Gorissen K, Kim M, Lehur PA, Lundby L, ET AL. European Society of Coloproctology guidance on the use of mesh in the pelvis in colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2021; 23:2228-85.