CASE REPORT

Necrotizing soft tissue infection of the abdominal wall secondary to descending colon adenocarcinoma

Alejandro Mitidieri1, Isaac

León Morgunovsky2, Cristian Rodríguez1, Julio Lococo1

Proctology Service,

Hospital Churruca Visca. Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina

1 Staff Member

2 General Surgery Resident

ABSTRACT

Necrotizing soft tissue infections (NSTIs) are acute bacterial infections that

affect the skin and soft tissues; they are associated with necrosis and

destruction of the fascias. Although they are rare, they have a high mortality

rate, close to 40%.

There are few publications on NSTI caused by colon cancer. We present a 75-year-old female patient who consulted for pain in the left lumbar fossa, with blisters, heat, and redness of the skin. A CT scan showed gas bubbles in the abdominal wall secondary to a perforated tumor of the descending colon.

Soft tissue debridement and left colectomy were performed, with temporary closure of the abdomen and continuous aspiration of the wound. The patient was discharged 28 days after hospital admission.

Early diagnosis, urgent surgery in stages and prompt initiation of antibiotic treatment are fundamental pillars for the correct outcome of patients with NSTIs.

Keywords: necrotizing infection, perforated colon tumor, emergency surgery

INTRODUCTION

Necrotizing

soft tissue infections (NSTIs) are acute bacterial infections that affect the

skin and soft tissues. They are associated with necrosis and destruction of the

fascias.1

Although this entity is rare, it carries a high mortality rate, close to 40%.2,3 Publications on NSTIs caused by colon cancer are scarce.4 We present a rare case of NSTI of the abdominal wall secondary to a perforated tumor of the descending colon.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence: Alejandro Mitidieri: alemitidieri@hotmail.com

Received: December 2021. Accepted: October 2022

Alejandro Mitidieri: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2368-1868, Morgunovsky Isaac León: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1231-8839, Julio Lococo: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5279-8526,

Cristian A. Rodríguez: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7582-2664

CASE

A 75-year-old woman, with no relevant history, is being studied for anemia. Colonoscopy

reveals diverticula in the left colon and a fixed, non-negotiable angle 60 cm

from the anal verge. Double-contrast computed tomography (CT) of the chest,

abdomen, and pelvis shows uncomplicated diverticula in the sigmoid colon and

luminal narrowing of the descending colon, which is in close contact with the

anterolateral abdominal wall. Surgery is decided with the diagnosis of a tumor

of unknown etiology.

While the preoperative workup is being carried out, the patient comes to the emergency room with a 2-day history of left lumbar pain and symptoms of fever.

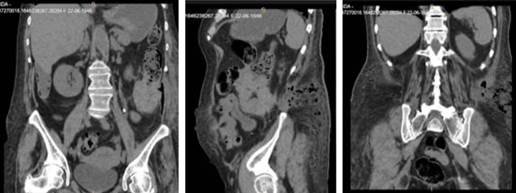

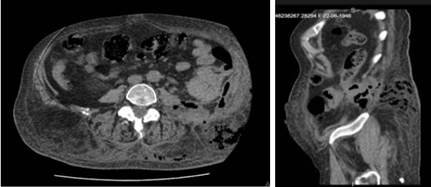

She is tachycardic, sweaty, dyspneic and febrile. On physical examination, a painful mass of skin and soft tissues was observed on the flank and left lumbar fossa, associated with blisters, warmth, and erythema. Laboratory tests reveal Hct 24%, Hb 7.6 gr/dL, WBC 37000/mm3, metabolic acidosis, increased lactic acid. The CT shows the well-known tumor of the descending colon, without a cleavage plane with the anterolateral wall of the abdomen and multiple air bubbles in the soft tissues of the left flank (Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5).

Figures 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. CT coronal, sagital and axial planes showing air bubbles in the soft tissues surrounding the colonic tumor.

Expansion with colloids and antibiotic therapy with ciprofloxacin and metronidazole were indicated, and emergency surgery was decided.

With the patient in the right lateral position, debridement of necrotic skin, subcutaneous tissue, and oblique abdominal muscles is performed, until vital and bleeding tissue is confirmed. A vacuum system with continuous suction is placed. The peritoneal cavity is approached by a midline laparotomy, finding a tumor in the descending colon attached to the lateral wall of the left flank. The colon is released, revealing a perforation. Segmental colectomy is performed with closure of the proximal and distal ends and temporary closure of the abdomen with a Bogotá bag, due to the patient's hemodynamic instability and metabolic acidosis, which requires damage control surgery.

The patient went to the ICU on ARM, requiring high doses of inotropics. With a clear improvement in her general condition, she was re-explored in the operating room at 24 and 48 hours. Devitalized soft tissues are debrided. No collections are found in the abdominal cavity. Extended left colectomy with right transverse colostomy is performed. Wall closure with mesh (Figures 6, 7, 8 and 9)

Figure 7.

Perforated

colonic tumor released. Figura 6. Colonic

tumor adhered to anterolateral abdominal wall.

|

The

continuous vacuum aspiration system was used and the dressings were changed

every 48 or 72 hours. The wound culture was positive for E.Coli Blee, sensitive

to the antibiotics received. The patient evolved torpidly, with prolonged

hospitalization, and she was discharged 28 days after admission (Figs. 10 and

11).

Figure 11. Granular

soft tissue wound on the left flank at hospital discharge. Figure 10.

Small dehiscence in the lower third of the abdominal wound at discharge.

Histopathology reported a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, with clear margins, 0/16 lymph nodes.T4N0M0.

The patient is currently undergoing chemotherapy treatment. In follow-up for plastic surgery to perform a skin graft on the flank wound.

DISCUSSION

Despite recommendations and guidelines regarding colorectal cancer (CRC)

screening, in the US 15-20% present with obstruction or perforation. Perforated

CRC has an incidence of 2-9%2 and it is the second cause of emergency

surgery for colon adenocarcinoma, with an incidence of 2.6% to 12%. Perforation

usually occurs at the tumor site due to the necrosis generated by its growth in

the colon wall and the friability of the tissue.13 Perforated CRC

has higher perioperative mortality, greater local recurrence, and greater

probability of peritoneal carcinomatosis.6

NSTIs have a high mortality rate (20-40%) and rapid and severe progression.8 For its adequate treatment, it is important to make an early diagnosis and immediately establish broad-spectrum antibiotics and aggressive and urgent surgical treatment in order to reduce the high percentage of mortality.2,3,6,7,9

The outcome of patients with clostridial bacterial infections is different from those with infections by other germs.1 In our patient, the culture showed E. coli Blee, sensitive to empirically indicated antibiotics.

In patients with colonic perforation associated with septic shock, the concept of abbreviated laparotomy with initial control of the septic focus, temporary closure of the abdomen with a negative pressure system, and subsequent evaluation is very encouraging.12

Antibiotic treatment without debridement of necrotic tissue has a 100%

mortality 6,10 In our review of the literature, we found that the only variables associated with higher mortality were age and delay in surgical debridement.

for more

than 24 hours.9,11 In the present case, surgical cleaning of the

anterolateral abdominal wall was performed every 24-36 hours to ensure that the

soft tissue infection did not progress (Figs. 10 and 11) and a vacuum

aspiration system was performed to promote granulation.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the literature, we consider that there are certain patterns that must

be taken into account for the better outcome of this entity.

1. Promote screening for the early detection of CRC with any of the existing methods.2

2. Make an early and accurate diagnosis and act without delay in the treatment of skin and soft tissue necrotizing infections.1-9,11,13

3. Carry out an aggressive and extensive debridement, until leaving vital and bleeding tissue.1-9,11,13

4. Perform staged surgery and debridement and resection of necrotic or devitalized tissues as many times as needed. Use a vacuum wound compaction system between surgeries.4-6

5. Make "s" incisions to give plastic surgeons greater possibilities to perform reconstructive plastic surgery on the time they deem appropriate.6

6. In abdominal surgery perform an early examination. Depending on the degree of stability of the patient consider staged surgery with temporary closure of the abdomen for future reexplorations.12

7. Perform surgery with oncologic criteria, removing en bloc the entire mesocolon and the soft tissues involved by the perforated tumor.1-9

8. If possible, close the endopelvic fascia to separate the abdominal compartment from the wall.6

9. Work together with the ICU and the Infectious Diseases Service to provide multidisciplinary and comprehensive treatment.4

REFERENCES

1. Wallace HA, Perera TB. Necrotizing Fascitis. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL, 2021.

2. Levine EG, Manders SM. Life-threateaning necrotizing fasciitis. Cal Dermatol. 2005; 23:144-47.

3. Takakura Y, Ikeda S. Retroperitoneal abscess complicated with necrotizing fasciitis of the thigh in a patient with sigmoid colon cancer. World J Surge Oncol. 2009.

4. Sato K, Yamamura H. Necrotiziting fasciitis of the thigh due to penetrated descending colon cancer: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2018; 4:136.

5. A case of necrotizing soft tissue infection secondary to perforated colon cancer. Cureus.

6. Datta et al, Novel emergency management of descending colon cancer presenting with retroperitoneal perforation. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2014; 7:1.

7. Royall Australasian College of Surgeons. Perforated descending colon adenocarcinoma manifesting as necrotizing fasciitis.. ANZ J Surg. 2020.

8. Hsiao-Wen et al. Abdominal necrotizing fasciitis due to perforated colon cancer. Visual Diagn Emerg Med. Taipei, Taiwan.

9. UptoDate: Surgical management of necrotizing soft tissue infections. 2019.

10. Masood U, Sharma A, Lowe D, Khan R, Manocha D. Colorectal cancer associated with Streptococcus anginus bacteriemia and liver abscess. Case report. Gastroenterol, 2016.

11. Kalaivani V et al, Necrotizing soft tissue infection-risk factors for mortality. J Clin Diag Res. 2013; 7:1662-65.

12. Rodríguez C, Pedro L, Venditti D, Fantozzi M, Lococo J, Vecchio P, et al. Laparotomía abreviada y terapia de presión negativa para el cierre temporal del abdomen como tratamiento de la peritonitis diverticular Hinchey III/IV. Rev Argent Coloproct. 2019; 30:104-13.

13. Wadhwani N, Kumar D. Localised perforation or locally advanced transverse colon cancer with spontaneous colocutaneous fistula formation: a clinical challenge. BMJ Case Rep. 2018. Doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-224668.