SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA OF THE ANUS WITH LIVER METASTASIS DURING PREGNANCY.

Facundo Sebastián Carrasco1, Ignacio Pitaco2, Juan Manuel O’Connor3, Hernán Oxilia4, Ángel Miguel Minetti5

Sanatorio Trinidad Quilmes e Instituto Alexander Fleming, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1 Surgeon, student of the University Specialist Course in Coloproctology. Faculty of Medicine, Universidad de Buenos Aires. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4193-9562-

2 Staff surgeon, Sanatorio Trinidad de Quilmes. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8450-0488

3 Medical oncologist, Instituto Alexander Fleming. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6975-5466

4 Pathologist, Sanatorio Trinidad de Quilmes. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8992-7747

5 Adjunct Professor. Faculty of Medicine, Universidad de Buenos Aires. Head, Coloproctology Section, Sanatorio Trinidad de Quilmes. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1235-6904

Correspondence: Facundo Sebastián Carrasco. facundoscarrasco@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Anal cancer is a rare disease that contributes to 3% of gastrointestinal malignancies, with squamous cell carcinoma being the most frequent. It has local invasion and lymphatic spread. Distant metastases are rare and most frequently occur in the liver, lung, and bone. No publications have been found on the association of squamous cell carcinoma of the anus with distant metastasis and pregnancy, the reason for this communication.

Key words: cancer, anus, pregnancy, metastasis

INTRODUCTION

Anal cancer is a rare disease that contributes to 3% of gastrointestinal malignancies, with squamous cell carcinoma being the most frequent. Since the end of the last century there has been a notorious increase due to its relationship with infection by the acquired human immunodeficiency virus and the human papillomavirus (HPV),(1,2) Data from the United States mention an incidence of 10, 7 to 15.5 per 1,000,000 persons.(1-4) In 2021, some 9,000 new cases were estimated; however, the risk of suffering from the disease and mortality increase by 2 and 3% per year, respectively.(5)

Anal squamous cell carcinoma is a neoplasm of local and lymphatic progression. It rarely presents distant metastases, more frequently in the liver, lung, and bone.(3)

During pregnancy, it is common to find patients with genital and/or anal HPV. However, except for involuntary omission, no publications have been found that associate pregnancy with distant metastatic anal squamous cell cancer, the reason for this communication.

CASE

A 27-year-old patient, with no relevant past history, 26 weeks pregnant, consulted for anal pain and recent rectal bleeding.

Abdominal examination: Body mass index 28 kg/m2. The uterus is palpable two finger-widths above the umbilicus. Auscultation fetal heartbeat was normal.

Gynecological examination: Normal vaginal introitus. Cervical os closed and centered.

Proctologic examination: External hemorrhoids at 3, 6 and 7 hours. Digital rectal examination was painful. On the right posterolateral aspect of the anal canal at the level of the dentate line, an exophytic, rounded, hard tumor was palpable, 4.5 cm in diameter, fixed to muscle planes and bleeding easily. No lymph nodes are palpable in both inguinal regions.

Initial presumptive diagnosis: Rectal cancer with sphincter involvement.

Colonoscopy: A friable tumor was found on the right posterolateral aspect of the distal anal canal, adjacent to the sphincter, from which a biopsy was taken.

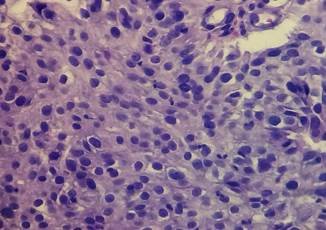

Histopathology: Poorly differentiated, infiltrating and ulcerated anal SCC (Fig. 1). Immunohistochemistry: P40 protein: (+), CK5 cytokeratin (+), CK20 cytokeratin (-), Homebox caudal protein CDX2(- ), diffuse P16 (+) protein.

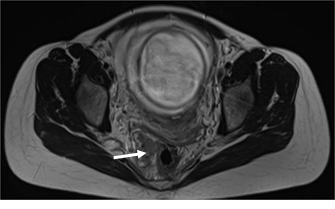

High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Isointense soft tissue lesion at the level of the anal canal with extension to the lower rectum, approximately 70 mm in length, without compromising neighboring organs. Multiple lymph nodes are seen in the mesorectal fat. Right internal iliac lymph node. Multiple hyperintense liver lesions are seen on T2-weighted imaging, consistent with metastases. (Figs. 2 and 3).

A multidisciplinary team decided to advance the pregnancy and mature the fetus by scheduling a cesarean delivery with abdominal exploration at 36 weeks.

Delivery/Cesarean section: Infraumbilical median laparotomy. Opening of the uterus on the cervical line. Delivery of a male child, weight 3,600 kg, APGAR 9. Extraction of the complete placenta. Hysterorrhaphy in one plane with absorbable suture. There are multiple liver metastases.

Follow-up: Postoperative without complications. One month after cesarean section, restaging with double-contrast computed tomography (CT) shows an increase in the number and size of metastases in both liver lobes, highlighting a new 15 mm metastasis in segment VII (Fig. 4). Enlarged anorectal lesion. Mesorectal lymph nodes in close contact with the rectum and mesorectal fascia. Two 10 mm lymph nodes (right hypogastric and left inguinal), are shown.

At the oncology meeting, treatment is proposed with a scheme of carboplatin AUC/5 (day 1) + paclitaxel 80mg/m2 (day 1-8, 15) every 28 days. Control laboratory on days 1 and 15.

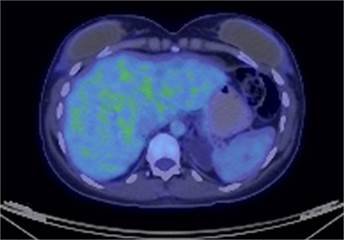

In the follow-up 5 months after starting treatment, the positron emission computed tomography (PET-CT) revealed involutional morphological changes with a slight increase in radiotracer uptake in the anal canal. There are anatomic and metabolic involution of liver, iliac and inguinal lesions (Fig. 5).

In the colonoscopy at 10 months, an indurated lesion of approximately 20 mm in diameter was observed on the anal canal at hour 6.

At 13 months, the PET-CT shows a 23 mm increase in anal metabolic activity predominantly on the left aspect. Multiple hypermetabolic lymph nodes in both supraclavicular fossa, posterior mediastinum, hepatic hilum, retroperitoneum, and pelvic and inguinal chains were present. Two hypodense nodular images with increased metabolism are visualized in the liver, 11 mm in segment VI and 6 mm subcapsular. Given these findings, second-line treatment was prescribed with 3 cycles of capecitabine and oxaliplatin.

In the last control at 16 months, after the 3rd cycle of the second-line regimen, the CT and the proctologic examination show a complete remission.

DISCUSSION

The usual behavior of anal SCC in its different degrees of differentiation is invasion of the submucosa, with more frequent metastases in the inguinal, iliac, and inferior mesenteric lymphatic chains, which present in around 30-40% at the time of diagnosis. More rarely, in less than 10% at the time of diagnosis and in 10-20% of patients treated with curative intent, distant metastases (liver, lung, bone, and skin) occur. These patients will have a poor prognosis, since the mean 5-year survival is 34.5%. (3,5,6)

Cancer and pregnancy have been defined as those tumors that appear during the gestation period and up to one year after the puerperium (7). The most common malignancies that occur during pregnancy are in order of frequency, breast tumors, melanomas, thyroid tumors, cervix tumors, lymphomas and colorectal tumors.(7)

The management of cancer during pregnancy poses real dilemmas and difficulties. Currently, the diagnosis is delayed due to the scarcity of symptoms and their confusion or underestimation. On the other hand, the timing of surgical or other treatment is not well established, and little is known about the risks that chemotherapy poses to the fetus in terms of malformations, miscarriage, and premature delivery. Finally, there is an ethical dilemma regarding whether to continue or terminate the pregnancy.

When making decisions, it is necessary to take into account the type, location and stage of the disease (localized disease, multivisceral invasion or distant metastasis), the general condition of the mother and the fetus, the treatment modality (surgery, chemotherapy , radiotherapy , immunotherapy) and the risk of postponing treatment until birth.

This patient was 26 weeks pregnant and presented an anal SSC with metastases in regional lymph nodes and liver, for which treatment with systemic chemotherapy was indicated. Given that the general fetal-maternal condition was good, delivery close, and fetal viability secure, it was proposed to delay treatment to avoid the risk of adverse events and to perform fetal maturation with cesarean delivery to allow intra-abdominal assessment of the disease.

Historically, the treatment for anal SCC was abdominoperineal resection with definitive colostomy. Starting in 1970, various studies established that in localized disease, treatment with chemotherapy and radiotherapy was superior to radical surgery in terms of local recurrence, overall survival, disease-free survival, and the need for ostomy.(8)

In 1997, Bartelink et al.,(9) published one of the first randomized studies, phase III, with 110 recruited patients, demonstrating that treatment with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin, with concomitant radiotherapy for 5 weeks, in patients with locally advanced disease , was superior to radiotherapy alone in terms of complete response, low local recurrence, high local and regional control, and long ostomy-free interval.

In 2018, Kim et al.(10) published the results of the Epitopes,HPV02 study, with 66 recruited patients. It is a phase II single-arm study of metastatic anal SCC treated for 3 weeks with docetaxel (6 cycles of 75 mg/m2 on the first day), cisplatin (75 mg/m2 on the first day) and fluorouracil (750 mg/m2 for 5 days). The same treatment was used with a modified regimen consisting of the administration for two weeks of docetaxel (8 cycles of 40 mg/m2 on the first day), cisplatin (40 mg/m2 on the first day) and fluorouracil (1200 mg/m2 daily during two days). Although there was no randomization, the authors demonstrated that both regimens achieved similar disease-free survival. However, the former showed a higher number of grade 4 adverse events, marking a potential first-line option in these patients.

More recently, Rao et al.(11) conducted a 2-arm randomized multicenter study in 91 patients, 45 treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel (80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, 15) in 28-day cycles and 46 treated with cisplatin (60 mg/m²) and fluorouracil (1000 mg/m² on days 1, 4) every 21 days. Both treatments were carried out for 21 weeks until disease progression or intolerance due to toxicity was detected.

The carboplatin + paclitaxel regimen compared to cisplatin + fluorouracil showed a better objective response rate (59 vs. 57%, respectively) and fewer adverse events (36 vs. 62%, respectively). Disease-free survival was 8.1 vs. 5.7 months and overall survival 20 vs. 12.3 months, respectively.

Based on these results, this has been the first-line regimen used in our patient. With this regimen, a complete remission was achieved at 5 months, although the relapse at 13 months made it necessary to indicate a second-line treatment with fluoruracil and oxaliplatin. After 3 cycles, in the last follow-up at 16 months, the patient is in complete clinical regression, by proctologic examination and images.

CONCLUSION

A case of anal SCC diagnosed during pregnancy is presented. The low frequency of this disease as a neoplasia associated with pregnancy with the addition of early metastatic disease stands out.

Treatment with the first-line paclitaxel and carboplatin regimen and second-line capecitabine and oxaliplatin show control of the disease 16 months after starting

Acknowledgement

We are especially grateful to Dr. José Bernal from Sanatorio Trinidad de Quilmes Imaging Service for providing the reports of the respective images.

References

1. Werner RN, Gaskins M, Avila Valle G, Budach V, Koswig S, Mosthaf FA, et al. State of the art treatment for stage I to III anal squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2021; 157:188-96.

2. Kin C. So now my patient has squamous cell cancer: diagnosis, staging, and treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal and anal margin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018; 31:353-60.

3. Shenoy MA, Winnicka L, Mirsadraei L, Marks D. Anal cancer with mediastinal lymph node metastasis. Gastrointest Tumors. 2021; 8:134-37.

4. Marref I, Romain G, Jooste V, Vendrely V, Lopez A, Faivre J, et al. Outcomes of anus squamous cell carcinoma. Management of anus squamous cell carcinoma and recurrences. Dig Liver Dis. 2021; 53:1492-98.

5. Young AN, Jacob E, Willauer P, Smucker L, Monzon R, Oceguera L. Anal cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2020; 100:629-34.

6. Glynne-Jones R, Nilsson PJ, Aschele C, Goh V, Peiffert D, Cervantes A, et al. Anal cancer: ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014; 25 Suppl 3:iii10-20.

7. McCormick A, Peterson E. Cancer in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018; 45:187-200.

8. Nigro ND, Vaitkevicius VK, Considine B Jr. Combined therapy for cancer of the anal canal: a preliminary report. Dis Colon Rectum. 1974; 17:354-56.

9. Bartelink H, Roelofsen F, Eschwege F, Rougier P, Bosset JF, Gonzalez DG, et al. Concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy is superior to radiotherapy alone in the treatment of locally advanced anal cancer: results of a phase III randomized trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Radiotherapy and Gastrointestinal Cooperative Groups. J Clin Oncol. 1997; 15:2040-49.

10. Kim S, François E, André T, Samalin E, Jary M, El Hajbi F, et al. Docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil chemotherapy for metastatic or unresectable locally recurrent anal squamous cell carcinoma (Epitopes-HPV02): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018; 19:1094-106.

11. Rao S, Sclafani F, Eng C, Adams RA, Guren MG, Sebag-Montefiore D, et al. International rare cancers initiative multicenter randomized phase II trial of cisplatin and fluorouracil versus carboplatin and paclitaxel in advanced anal cancer: InterAAct. J Clin Oncol. 2020; 38:2510-18.

|

Figure 1. Histopathology (H&E x 400). Atypical features of neoplastic proliferation are observed in detail. Cells exhibit epithelial appearance, cohesive layering, macrokaryosis, hyperchromasia, and loss of nuclear polarity and acidophilic cytoplasm. Although there is no evidence of keratinization, no formation of glandular microlumina is observed, which favors the diagnosis of a non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma.

|

Figure 2. High-resolution MRI. Axial T2-weighted

image showing an isointense lesion at the level of the rectum, between 10 and

11 hours, that extends towards the mesorectal fat (arrow), close to the fetal

head.

|

Figure 3. High-resolution MRI. Sagital T2-weighted image. Multiple hyperintense liver lesions (arrow), attributable to secondary dissemination of anal squamous cell carcinoma.

|

Figure 4. CT scan, coronal plane, performed 1 month after cesarean section, showing multiple liver metastases (arrow), increased in number and size compared to those seen on MRI at diagnosis.

A

Figure 5. PET-CT performed 5 months after starting treatment shows absence of the radiotracer in the liver.